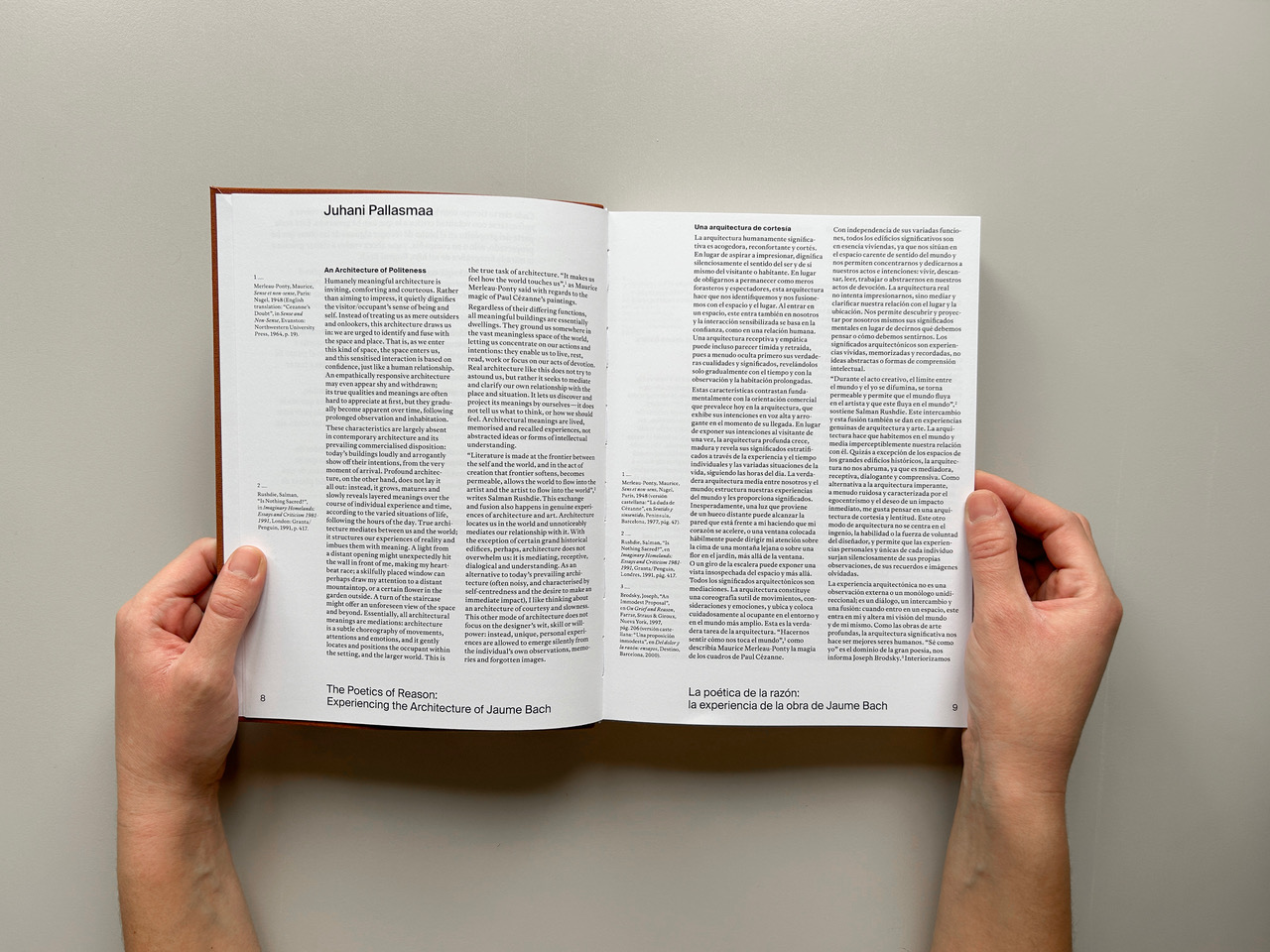

Lessons in time. Eugeni Bach

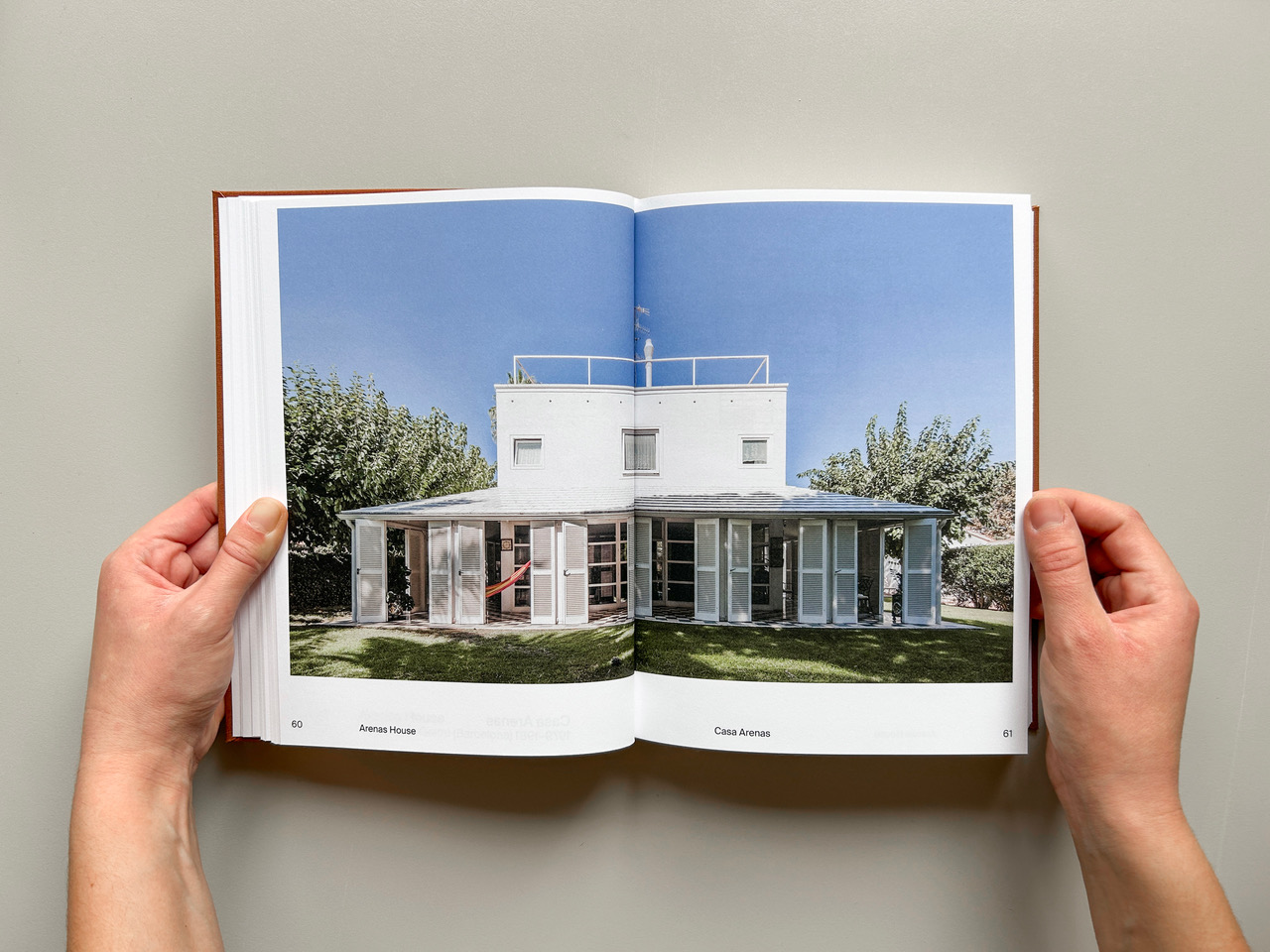

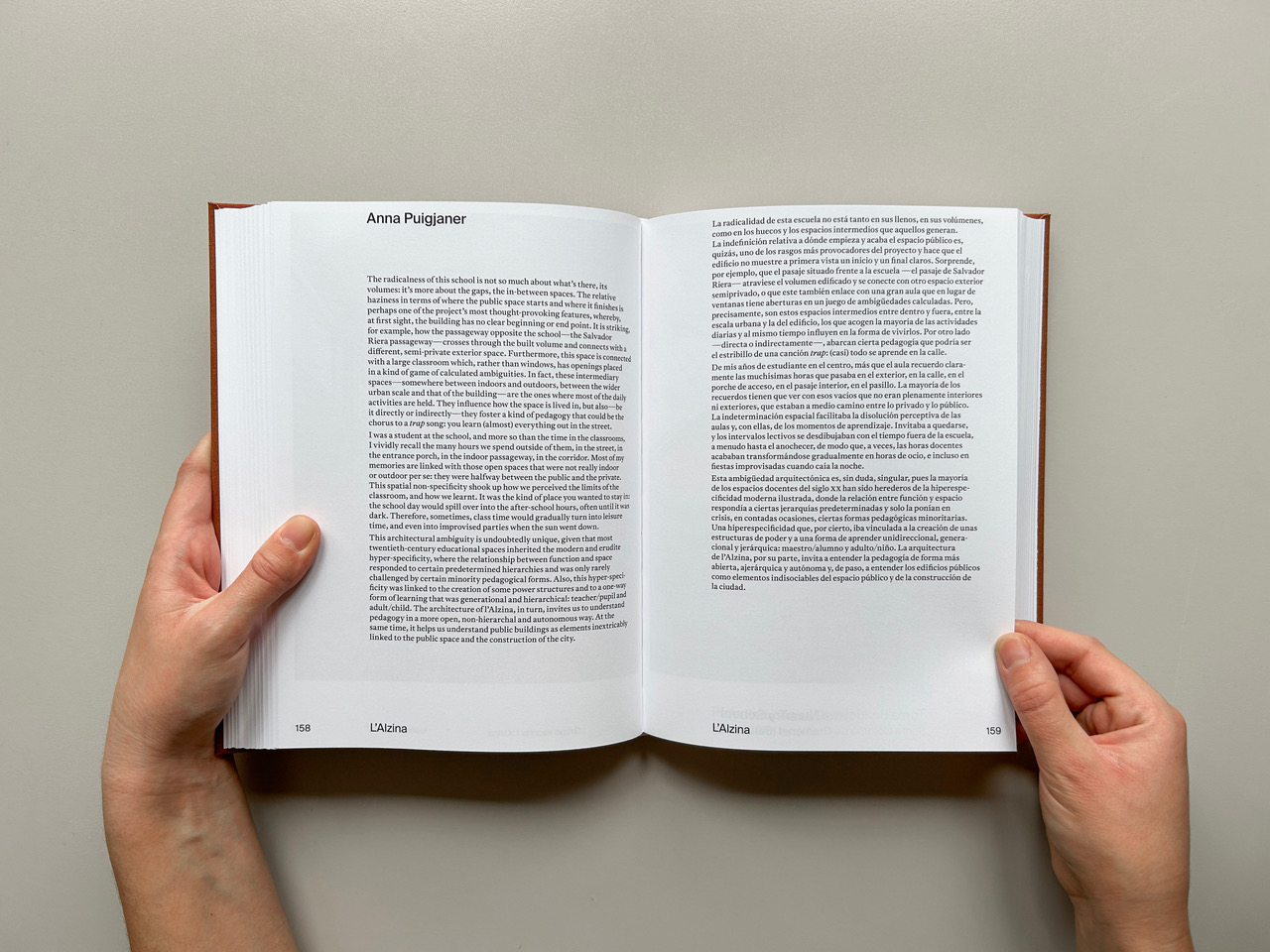

There are two main reasons for revisiting a work of architecture: one of them has to do with the work itself, while the other is about us. On the one hand, a revisit lets us see the effects of time, to observe how the work has coped with the changes over the years and whether it is ageing with dignity. On the other hand, it reveals how we have changed too: we might realise there are certain parts of it that we overlooked years ago—aspects that fell outside of our scope of interest at the time, perhaps—but that we now focus on more keenly. Over the last four years, I have revisited over fifty of my father’s works (not all of which are included in this volume). It has been a revelatory experience, and this tour has thus turned into a series of lessons

on architecture, both in terms of how the passage of time has affected the works in question, but also regarding what they have taught me, in some cases many years since I first visited them.

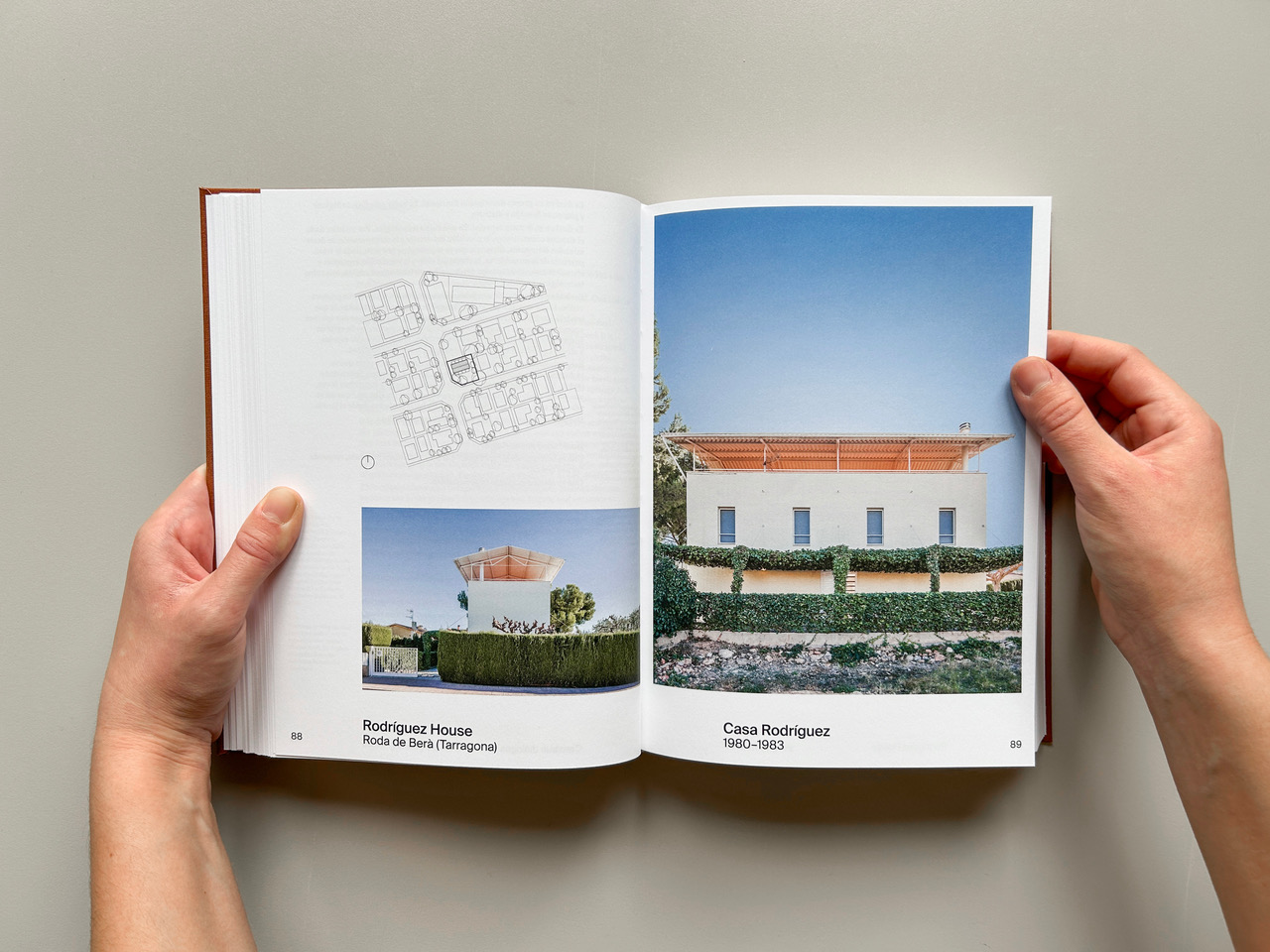

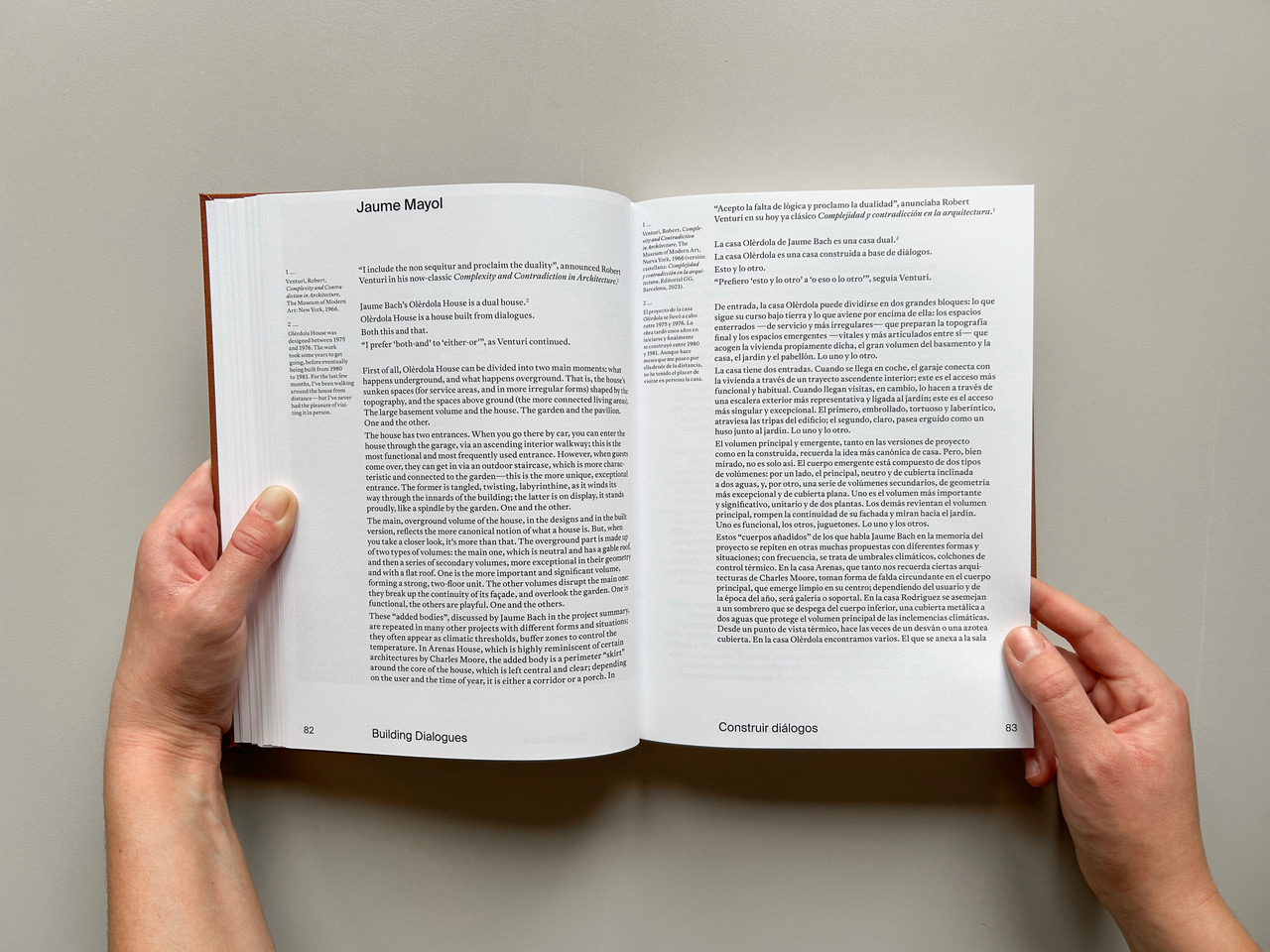

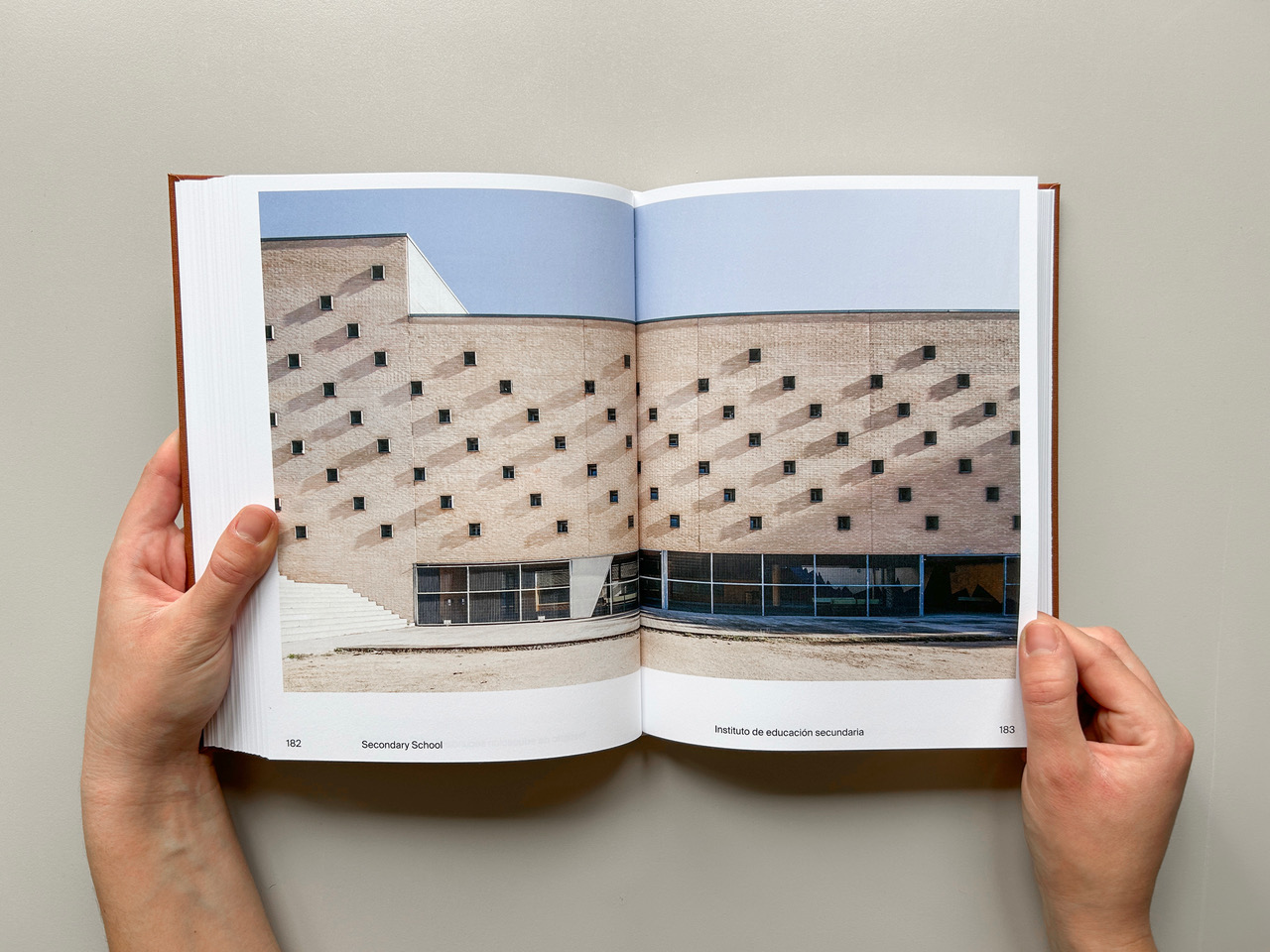

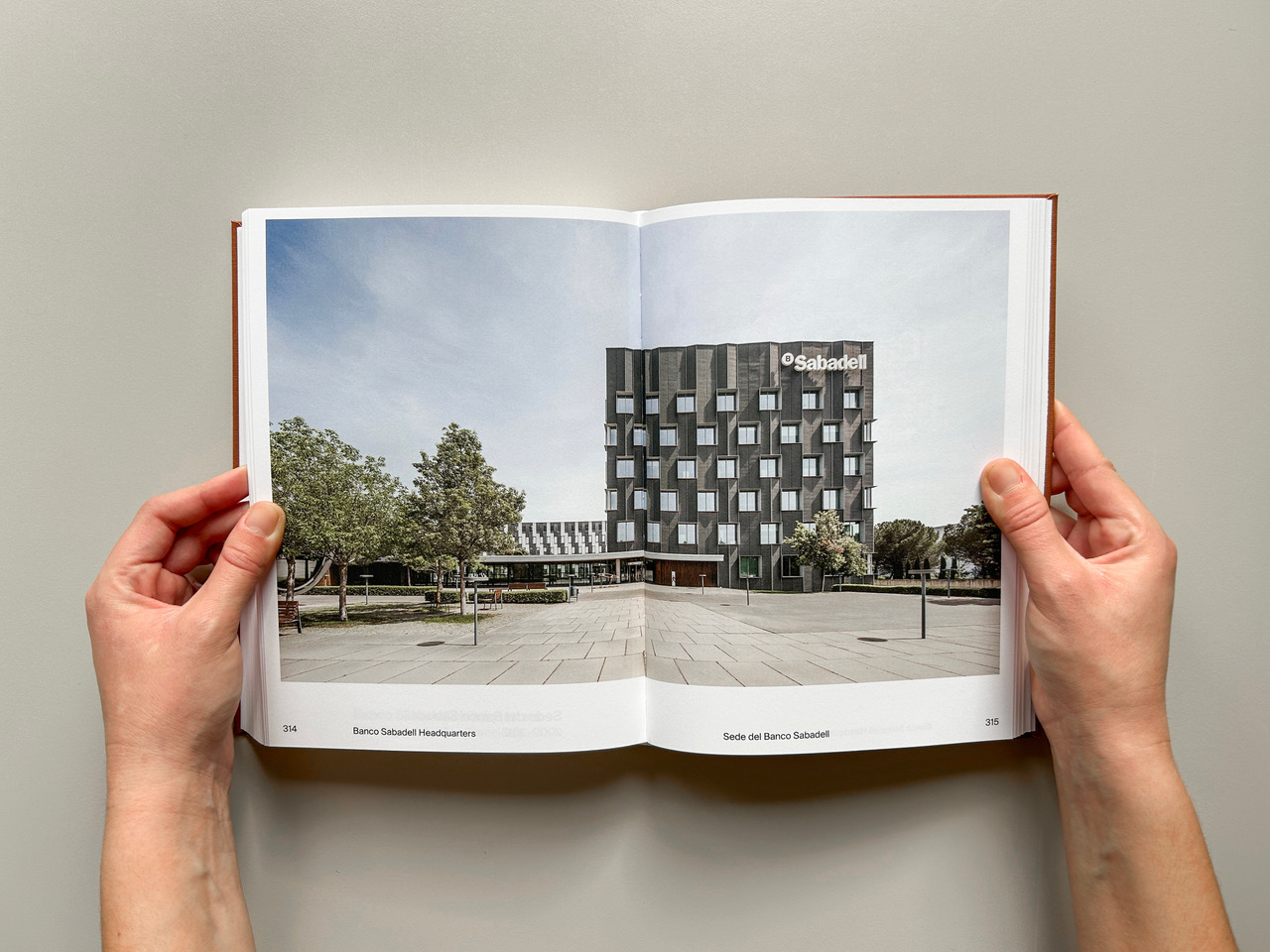

Of all the lessons I’ve learnt on the way, there are two reflections in particular that I believe perfectly sum up both my father’s architecture and the tone that comes through in this book. The first one is that the projects I visited are holding up really well against the passage of time, both materially—because they were designed with their use and ageing in mind—and conceptually. It is not easy to determine how old these projects are, probably because they were conceived of with a timeless character that sets them apart from fleeting fashions and conventions; if we didn’t know, we’d struggle to pinpoint which decade they were built in.

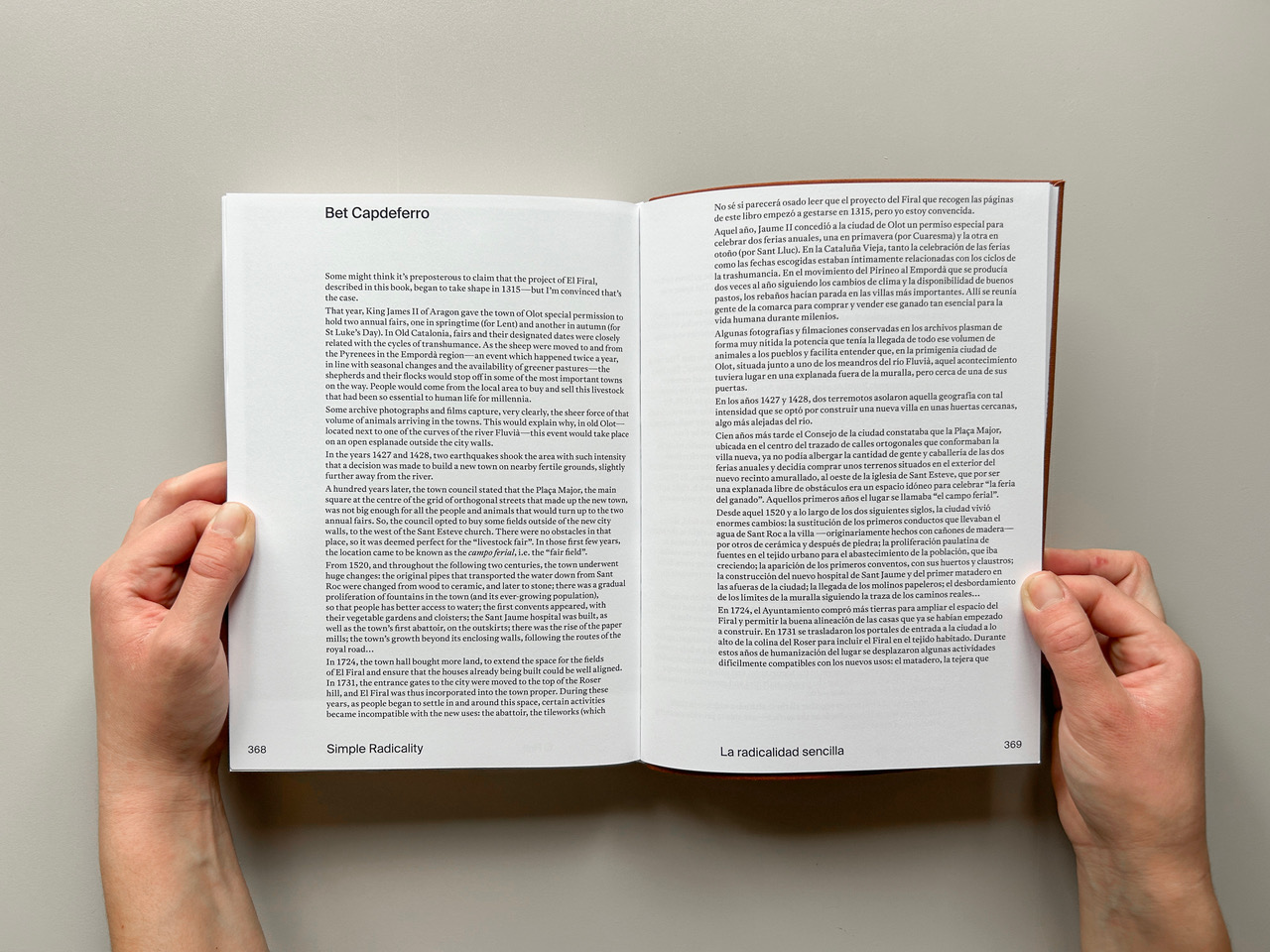

The second lesson is that these works were designed to be lived in, and they have formed close emotional bonds with their users. Most of the single-family homes still belong to the clients who commissioned them; the changes made since then—if any have been made at all—have been minimal, and they show a degree of care and a relationship more like that of a lifelong partner.

Such a personal bond is understandable with a single-family home—even if it’s simply because the users have grown up and spent their life there—but, surprisingly, the same thing had also happened in many of the public buildings I visited: school head teachers who insist on giving us a tour of the building, with great pride; residents who explain the project and everything they like about it; janitors who still remember that a different project by Jaume Bach won the FAD Award the same year that

“their building” was a finalist too, even though their one was better!

Re-photographing all these projects is a way to capture snapshots of those lives; publishing them is a good opportunity to show a way of thinking and living architecture, an approach to design that—rather than denying it, as is so often the case—actually embraces time itself as a tool of the project.