The movement between rooms is as important as the rooms themselves; and its arrangement has as much effect on social interaction in the rooms, as the interiors of the rooms.

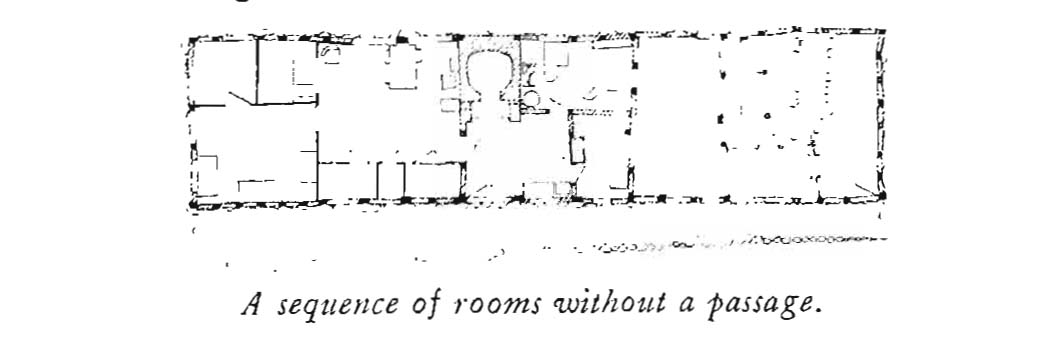

The movement between rooms, the circulation space, may be generous or mean. In a building where the movement is mean, the passages are dark and narrow—rooms open off them as dead ends; you spend your time entering the building, or moving between rooms, like a crab scuttling in the dark.

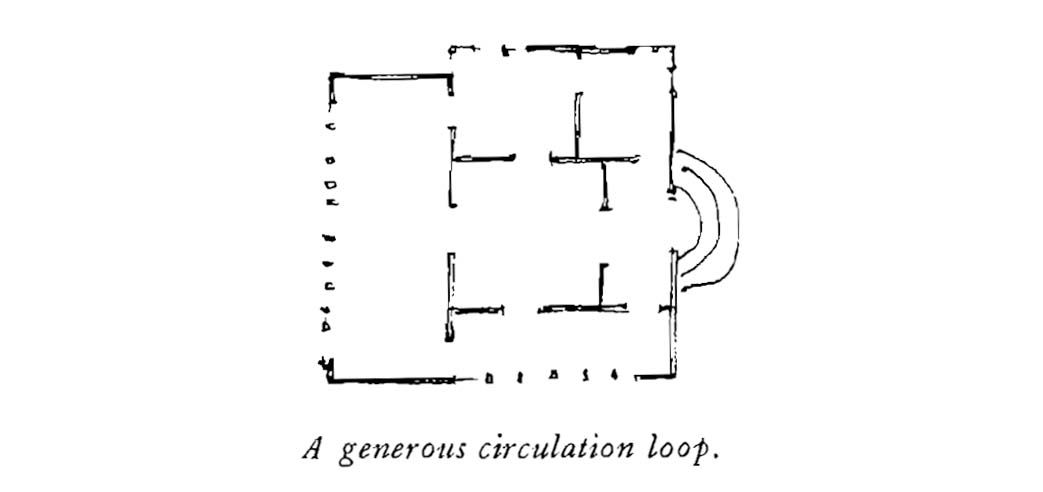

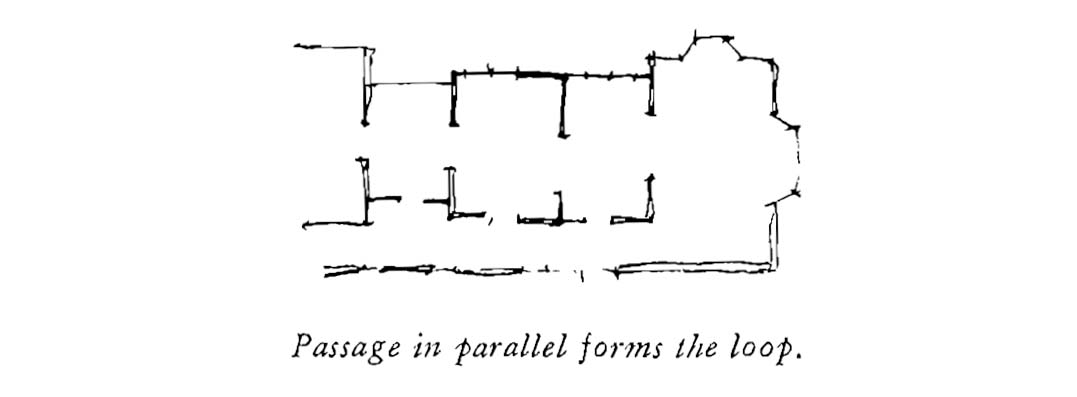

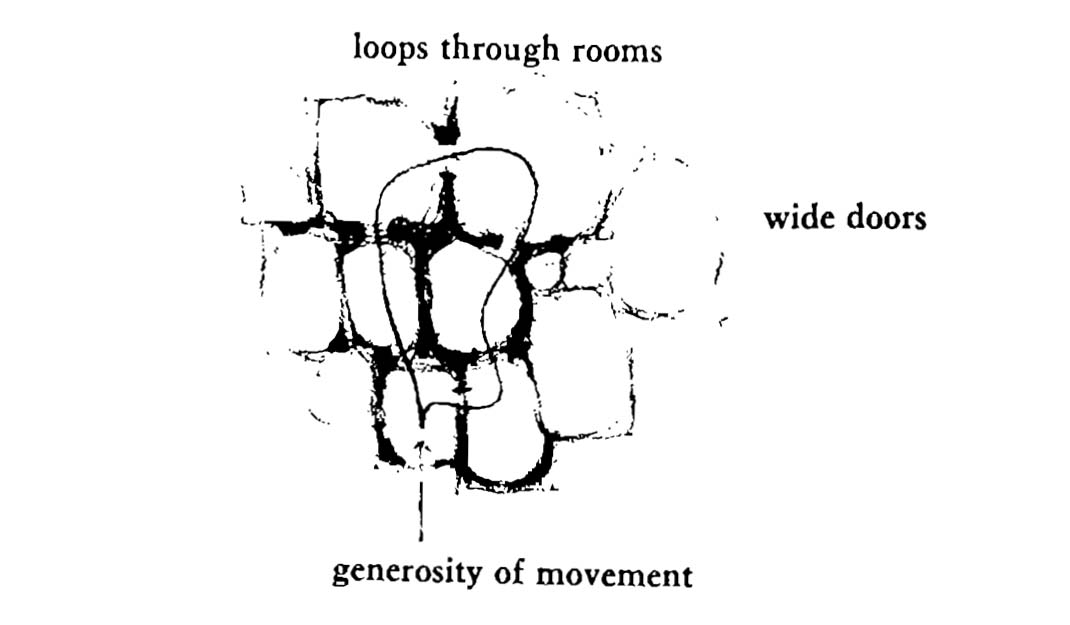

Compare this with a building where the movement is generous. The passages are broad, sunlit, with seats in them, views into gardens, and they are more or less continuous with the rooms themselves, so that the smell of woodsmoke and cigars, the sound of glasses, whispers, laughter, all that which enlivens a room, also enlivens the places where you move.

These two approaches to movement have entirely different psychological effects.

In a complex social fabric, human relations are inevitably subtle. It is essential that each person feels free to make connections or not, to move or not, to talk or not, to change the situation or not, according to his judgment. If the physical environment inhibits him and reduces his freedom of action, it will prevent him from doing the best he can to keep healing and improving the social situations he is in as he sees fit.

The building with generous circulation allows each person’s instincts and intuitions full play. The building with ungenerous circulation inhibits them. It not only separates rooms from one another to such an extent that it is an ordeal to move from room to room, but kills the joy of time spent between rooms and may discourage movement altogether.

The following incident shows how important freedom of movement is to the life of a building. An industrial company in Lausanne had the following experience. They installed TV-phone intercoms between all offices to improve communication. A few months later, the firm was going down the drain and they called in a management consultant. He finally traced their problems back to the TV-phones. People were calling each other on the TV-phone to ask specific questions —but as a result, people never talked in the halls and passages any more —no more “Hey, how are you, say, by the way, what do you think of this idea. . .” The organization was falling apart, because the informal talk — the glue which held the organization together— had been destroyed. The consultant advised them to junk the TV-phones —and they lived happily ever after,

This incident happened in a large organization, But the principle is just the same in a small work group or a family. The possibility of small momentary conversations, gestures, kindnesses, explanations which clear up misunderstandings, jokes and stories is the lifeblood of a human group. If it gets prevented, the group will fall apart as people’s individual relationships go gradually downhill.

It is almost certain that the building with ungenerous circulation makes it harder for people to maintain their social fabric. In the long run, there is a good chance that social order in the building with ungenerous circulation will break down altogether.

The generosity of movement depends on the overall arrangement of the movement in the building, not on the detailed design of individual passages. In fact, it is at its most generous, when there are no passages at al and movement is created by a string of interconnecting rooms with doors between them,