Whereas in our recent past the paradigm by which architecture was measured was the city, now, the collective reference surrounding our design activity is the relation with nature. (1)

Sustainability as an economic but also a moral and political argument is clearly a consensus in our societies. It is a frequently abstract, formless argument with religious overtones (appealing more to faith than to reason), utilizable in political verbalism and which drifts easily towards engineering technocracy.

In this context, a vindication of the presence of the four elements (earth, water, air, fire) by means of which the Presocratic philosophers envisaged humankind’s relation with nature seems extremely useful to the discipline today.

The elements relate us to nature as a physical phenomenon that can be experienced with the senses and is therefore directly connected with architecture, which, as we know, addresses the real construction of the world, the alchemic operation that turns concepts into material.

The elements save our activity from the pure mathematical abstraction on which technology is based.

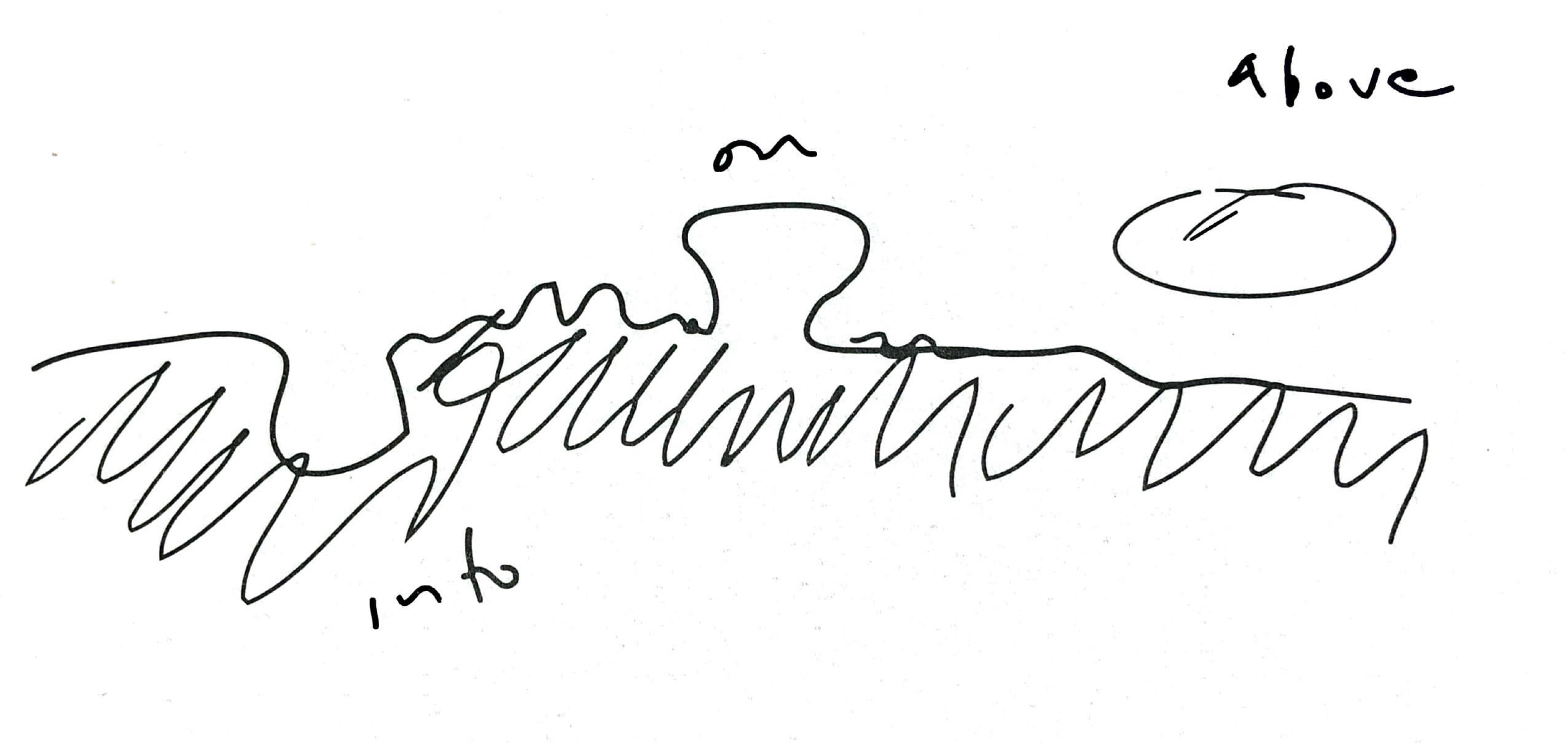

Our activity, at a primitive, archaic but present level consists in modelling the earth to geometrize its surface or piercing it to build foundations, erecting walls and roofs that protect us from rain and snow, and using the energy of fire as light and heat that make the resulting space habitable.

In the present-day state of globalization, in which the identity-modernity equation is appearing in a new light, the elements reproduced in all cultures as an initial moment with which human construction activity is related, form part of a general vocabulary of common arguments (2). Having ruled out modernization as the uncontrolled application of the tired old prototypes of the metropolis, the intelligent, sensible manipulation of the elements provides the basis for specific projects that are, at once, rooted and globally comprehensible.

At an initial stage of project development, the relation with the elements as the origin of the project refers us to archetypes: pure protection, the bunker (echoes of Paul Virilio) or the cave. At the other extreme, the fragile tent of the nomad (remember Buckminster Fuller and the dabblings of the 1960s). In the Romantic tradition (on which all of this argumentation is based), the ruin and, in general, the expressive value of the unfinished, of what has been undone yet is still to be done, also emerges as a possibility.

This is a book produced in the warmth of the teaching experience, which uses this ephemeral (and, for the student, initial) encounter with the project as a material which, divested of the anecdotal, can be elevated to category.