Dear Future Architect,

I love stories. I love myths.

To me they conjure images in my mind.

Often they sound impractical but I see in them the flight of imagination.

And to me, this imagination is what life stands for, not necessarily tangible, touchable, but an unknown spirit that makes the heart throb. It is this aspect that excites me.

I feel like a child when I read or hear a myth. This in turn loosens my sense of logical, functional upbringing.

Suddenly my sense of logic and my sense of what I have learnt as an architect disappear. An urge to become one with fiction takes over.

I start imagining so-called fictional, illogical, often impractical events and situations. This is what I have done all my life.

I create and conceive a mythological or fictional story, loosen up all sense of the measurable and thus discover in each line, each volume, each function, some illogical moment where the most unexpected event may happen.

With this, my conceptual plan, form, structure, I begin to create an accidental and unpredictable situation. Often to my colleagues and even to myself it is unexpected. But I realise in this unexpected formation, a new creation emerges like a new animal creature in a zoo.

Losing all sense of my professional logic at these times, I am sometimes scared, but over time I realise that I have found in this new configuration an unexpected world, full of diverse experiences often logically impractical.

So my suggestion to all of you is to always recall your childhood, don’t grow too rigid and take a chance to rejoice in what unknown product you have created.

Lastly, history is created by breaking ground, challenging our yesteryears.

Doshi

Gujarat, India

26 May 2020

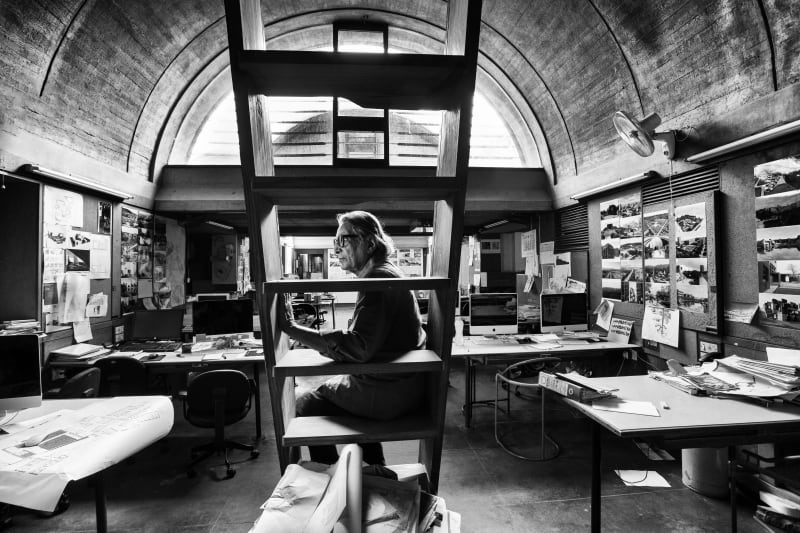

SANGATH : AN EMBLEM OF DOSHI’S PHILOSOPHY

The real breakthrough came with Sangath, (1979-81) Doshi’s own studio on the edge of the countryside to the west of Ahmedabad — a green enclave of grassy mounds, steps, terraces, water cascades and earth-hugging vaults covered in chips of china mosaic to reflect glare and heat. “Sangath” means “moving together through participation” and the place is more than just an architectural office. At the back of Doshi’s mind there may have been memories of the atelier at 35 Rue de Sevres where the line between work and education had never been firmly drawn.

(Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India; William J. R. Curtis)

Sangath is a key project that takes Doshi from an explicitly rational and objective approach to architecture toward an openly oneiric and mythopoeic way of working. […]

As a stalwart of the first generation of Indian architects to emerge following national independence in 1947, Doshi took on the enormous task of graduating India into a “brave, new world,” as proposed by the first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Since then, through a powerful body of work, Doshi has been instrumental in framing a modern architectural idiom and ethos for the country. This was made possible through his personal commitment to nation-building and a unique background, with two of the foremost form-makers of the modern period. […]

Besides his intimacy with both [Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn] the mission and realization of modern architecture, Doshi has remained deeply in touch with the ethos of India’s ancient civilization.

He continues to reflect on and draw inspiration from the vast repertoire of Vedic and Hindu traditions. It is this presence of two civilizational and philosophical strands in Doshi’s work that has always offered new possibilities and excursions, as well as debates, in the evolution of modern Indian architecture. What distinguishes Sangath from Doshi’s earlier projects is a more unabashed narrative of the Indian strand as well as a deeply personal mythography.

(Essay; Kazi Khaleed Ashraf)

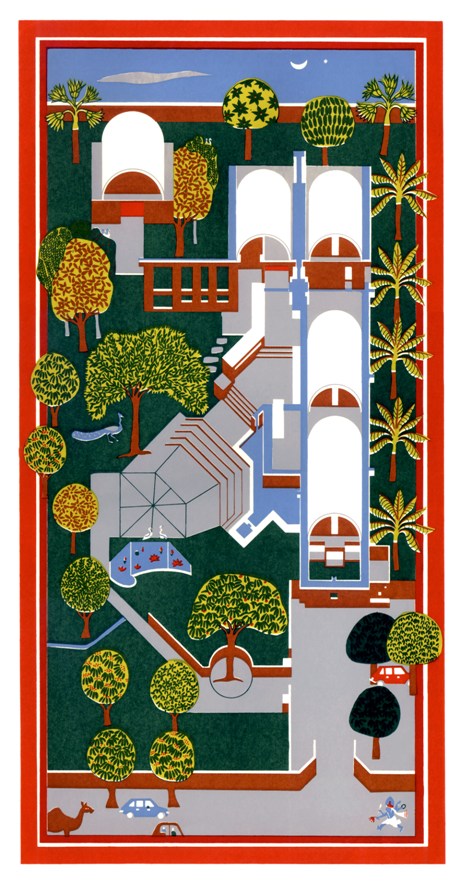

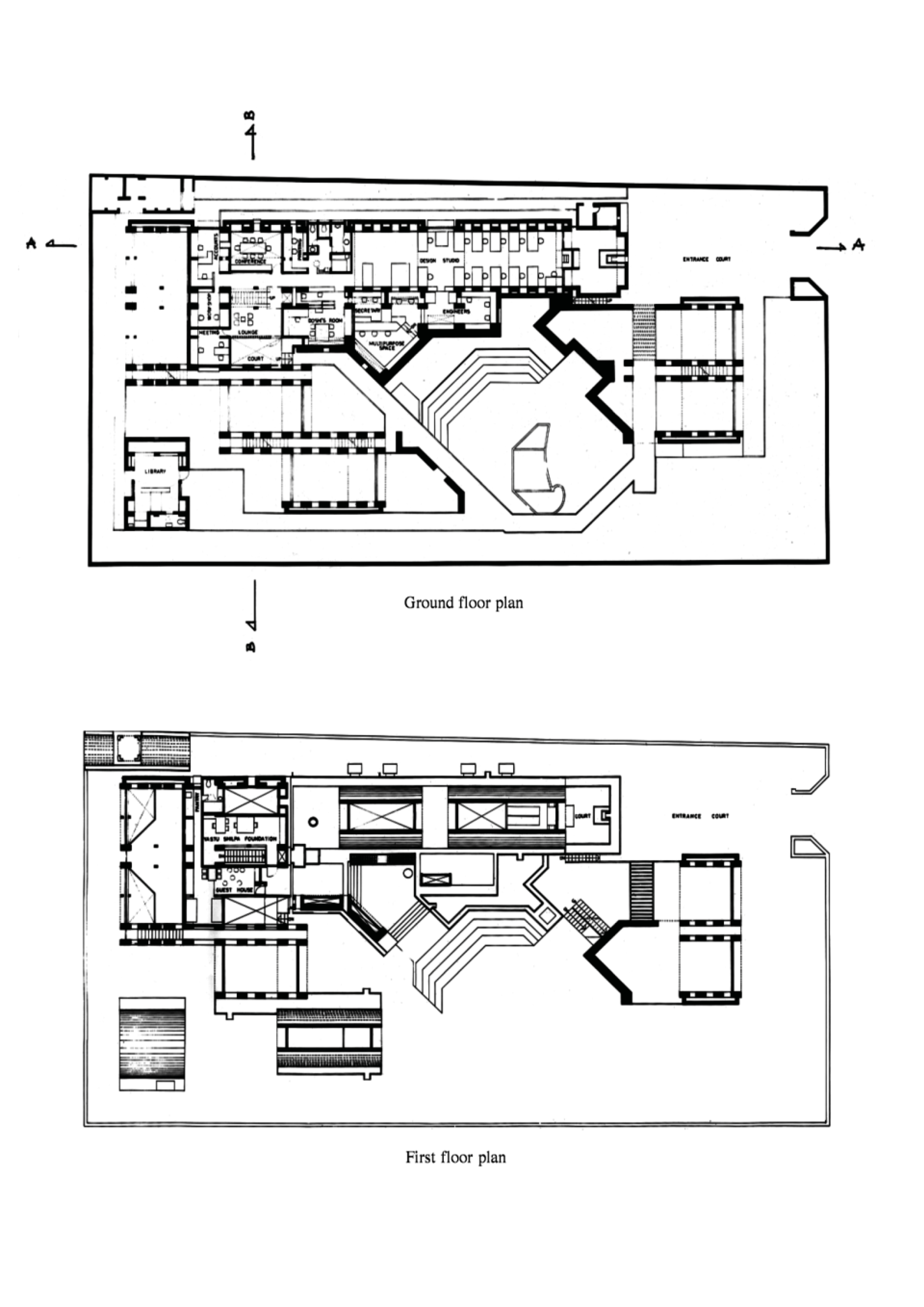

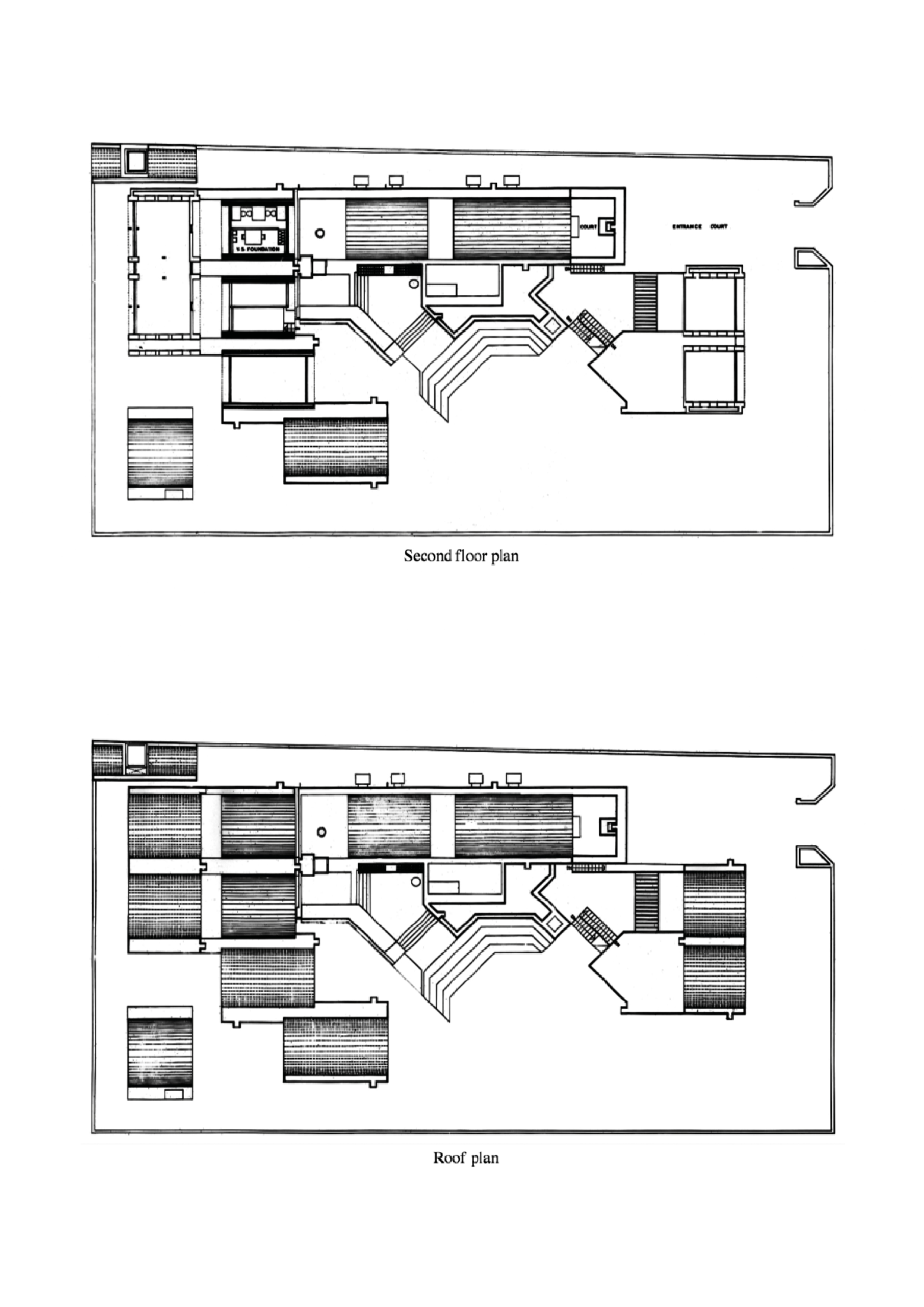

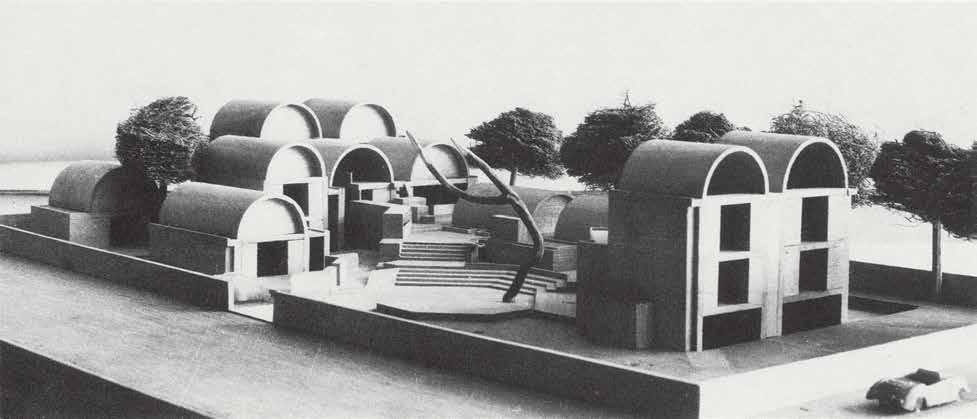

The site was a quadrangle looking south over a road towards open country […].

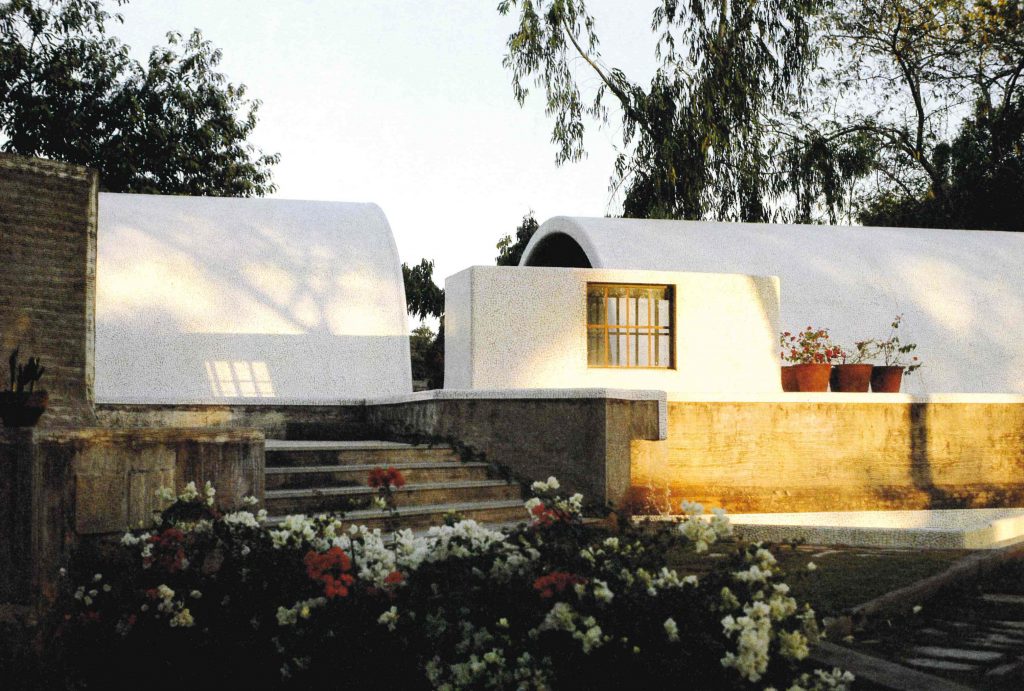

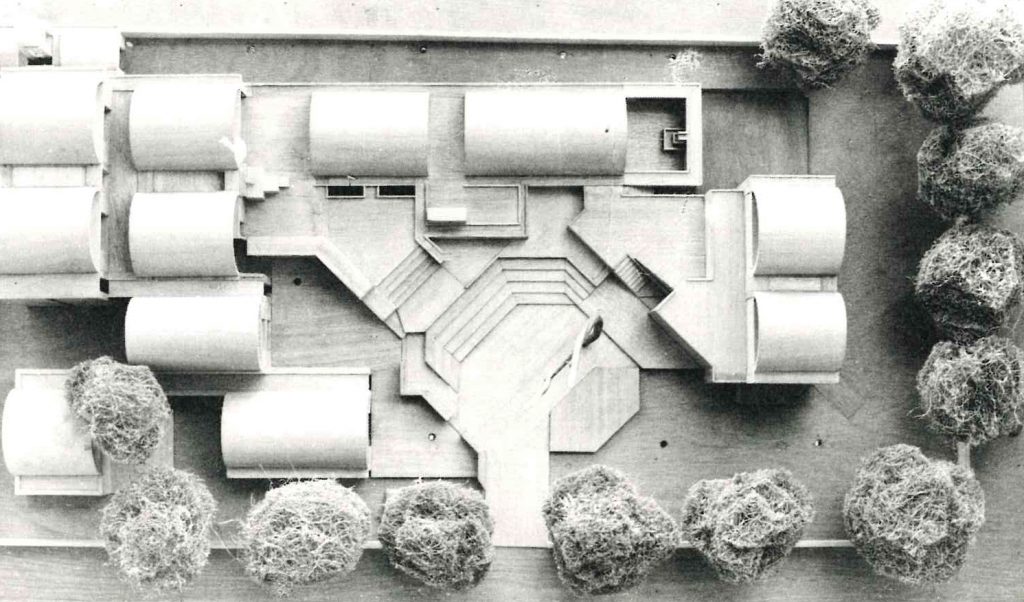

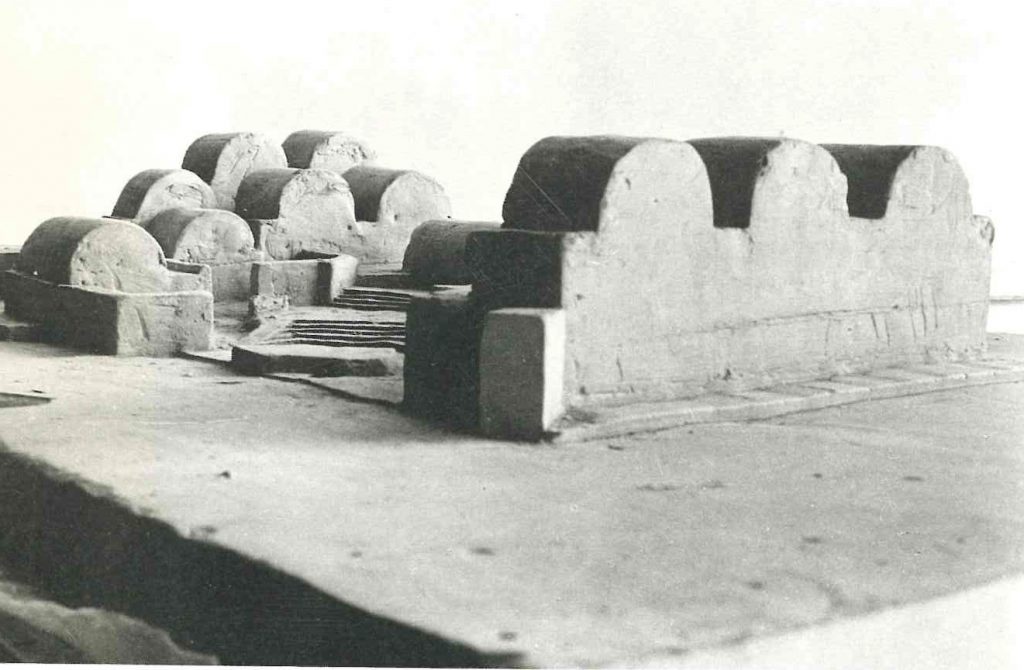

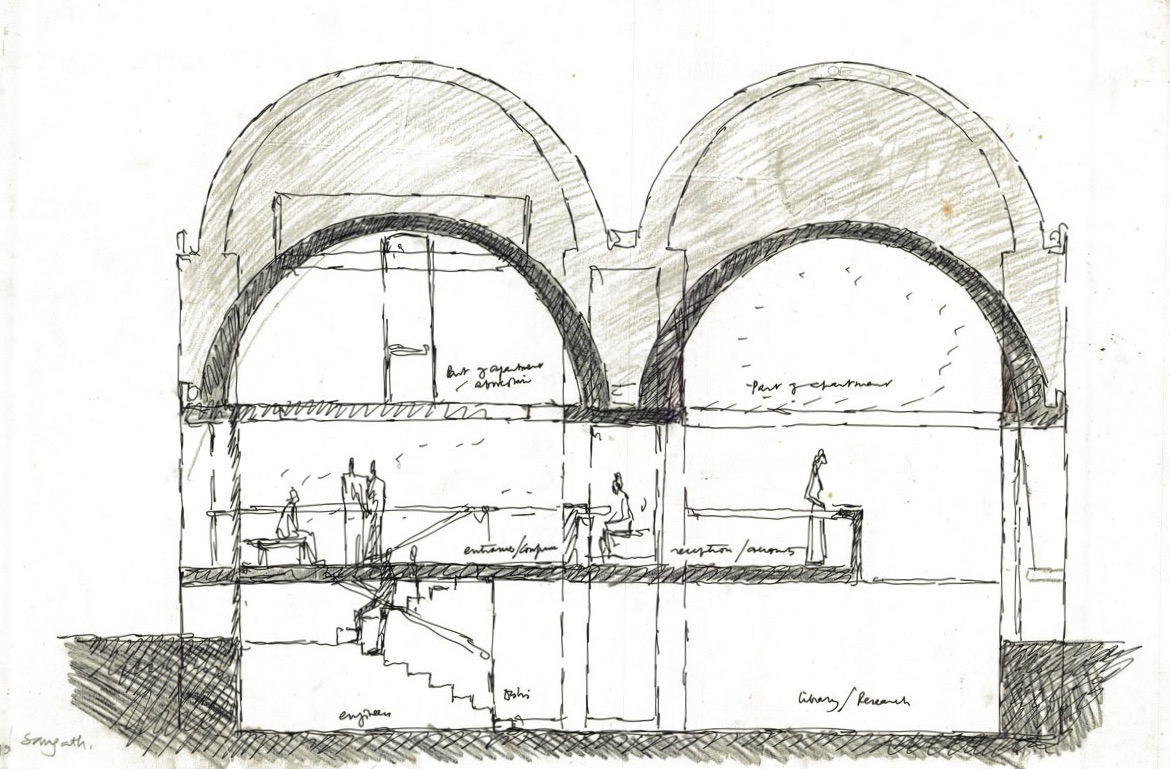

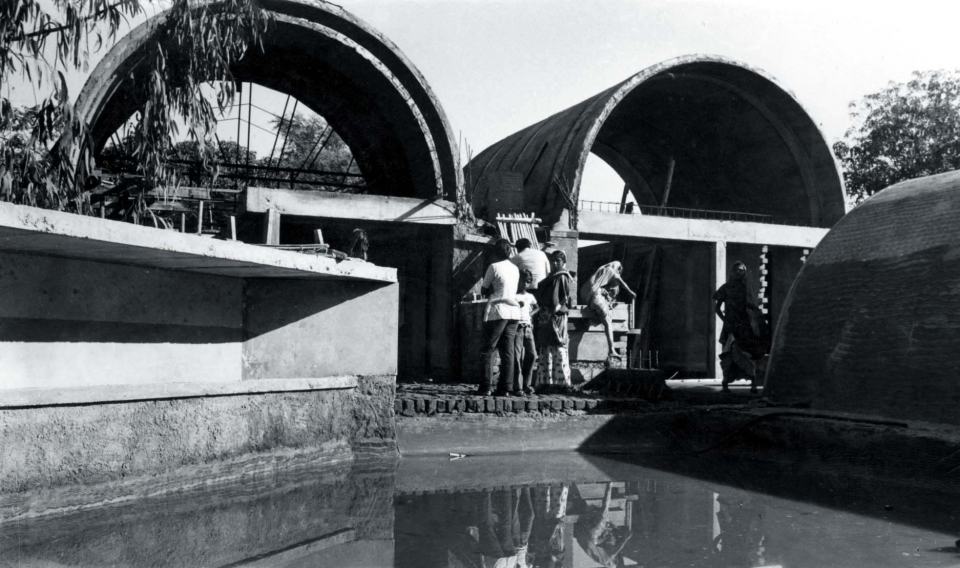

Early in his design process Doshi decided to sink the main studio partly below ground, to protect it from the fierce heat, to maintain a low silhouette and to accommodate a middle level terrace at an easy distance and height from the garden. The visitor is welcomed to Sangath by a shallow cascade of grassy steps that make ah informal amphitheatre.

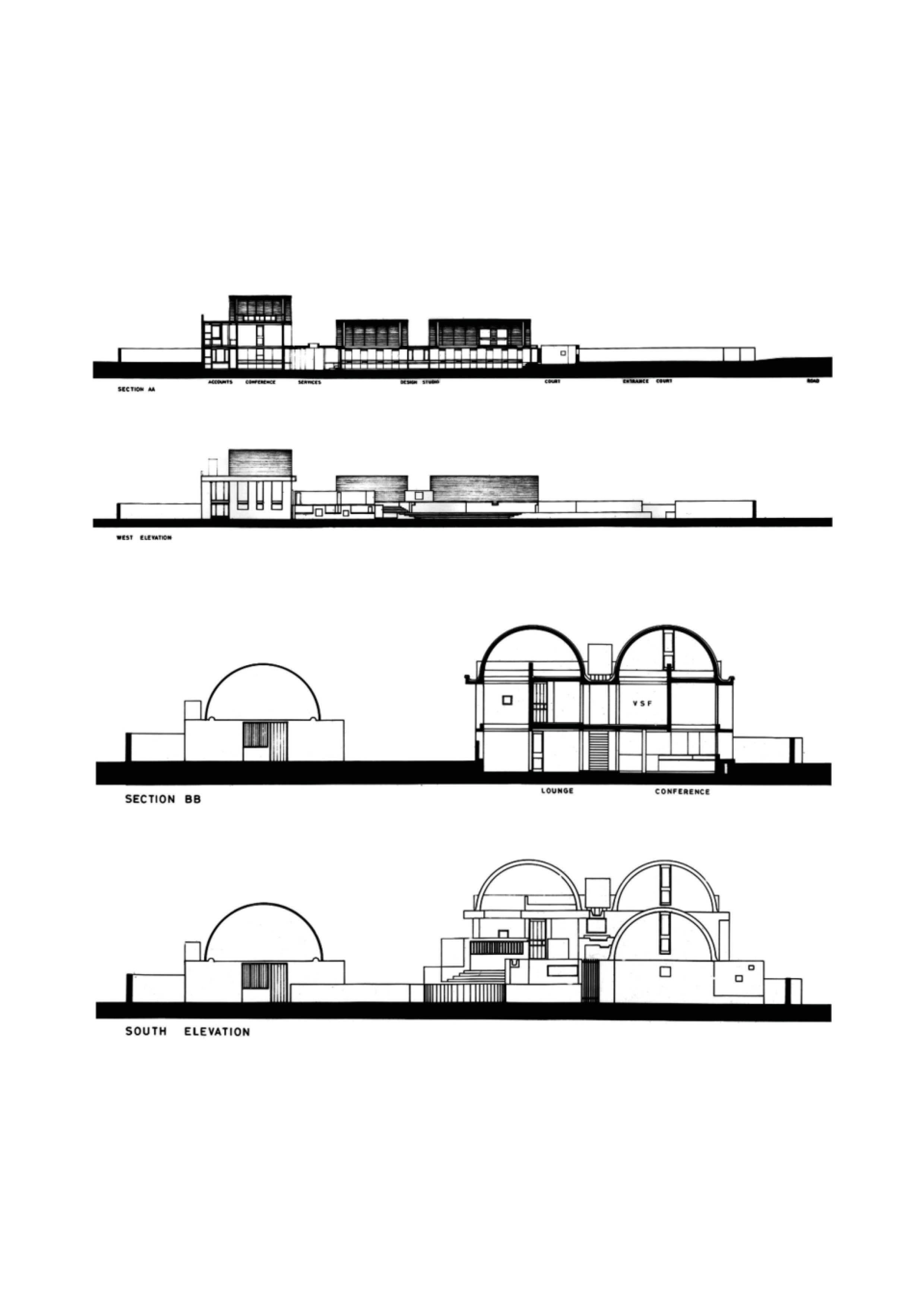

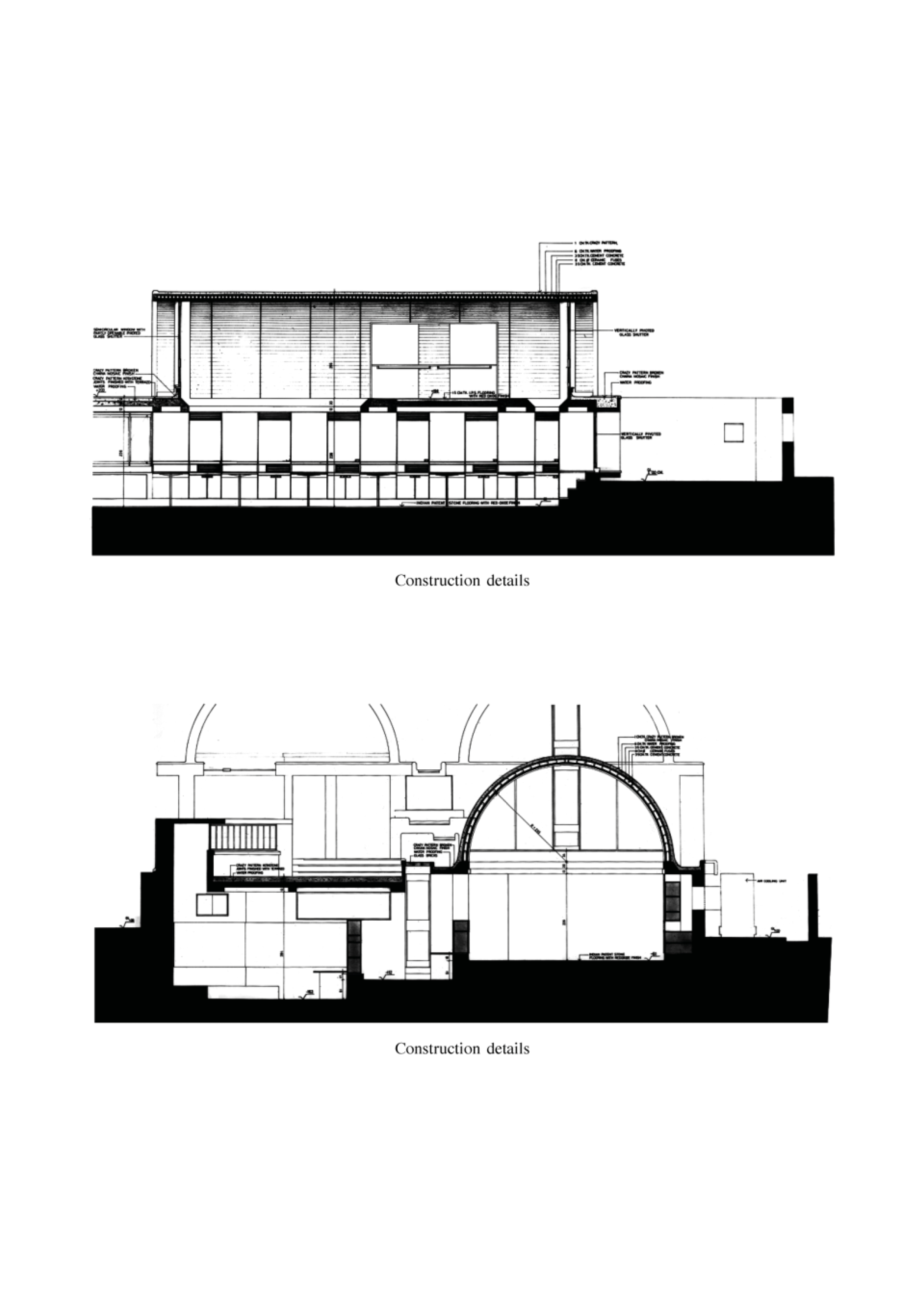

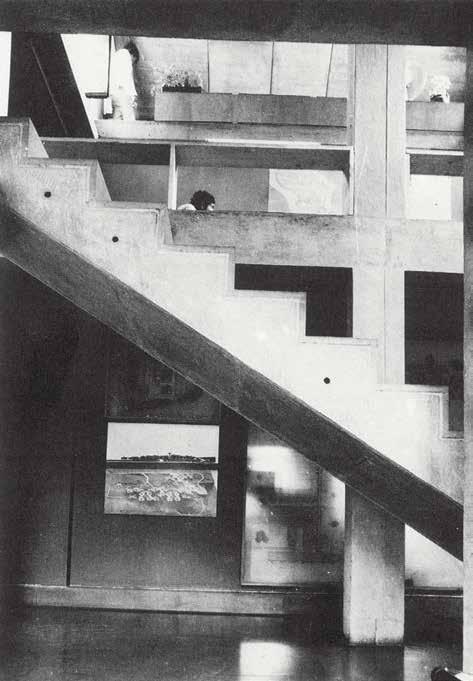

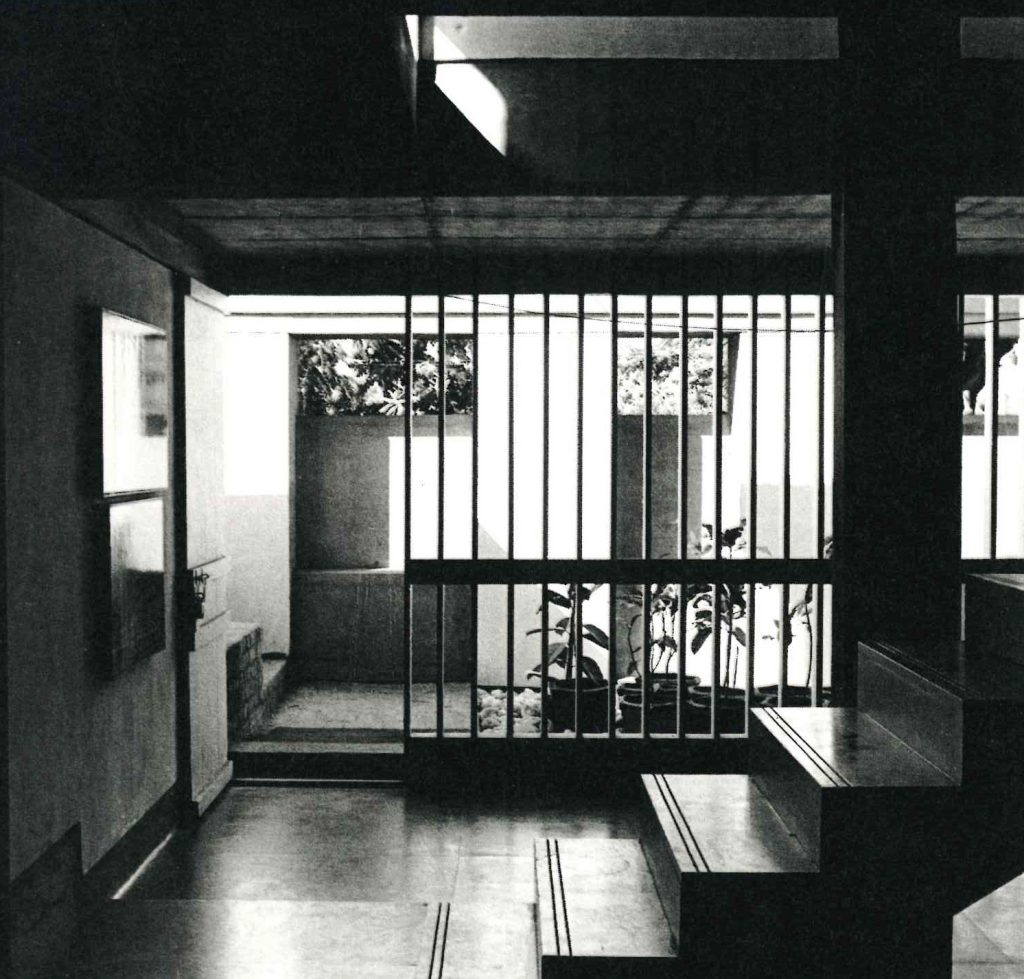

A lateral section through the building shows how various internal levels are interlocked beneath the vaults to make a 20th century version of a primaeval dwelling. A plan reveals a collage of longitudinal rectangular and flange-shaped rooms linked ambiguously to one another through screens of structure including piers and walls placed at varying intervals to give a syncopated rhythm to the interiors.

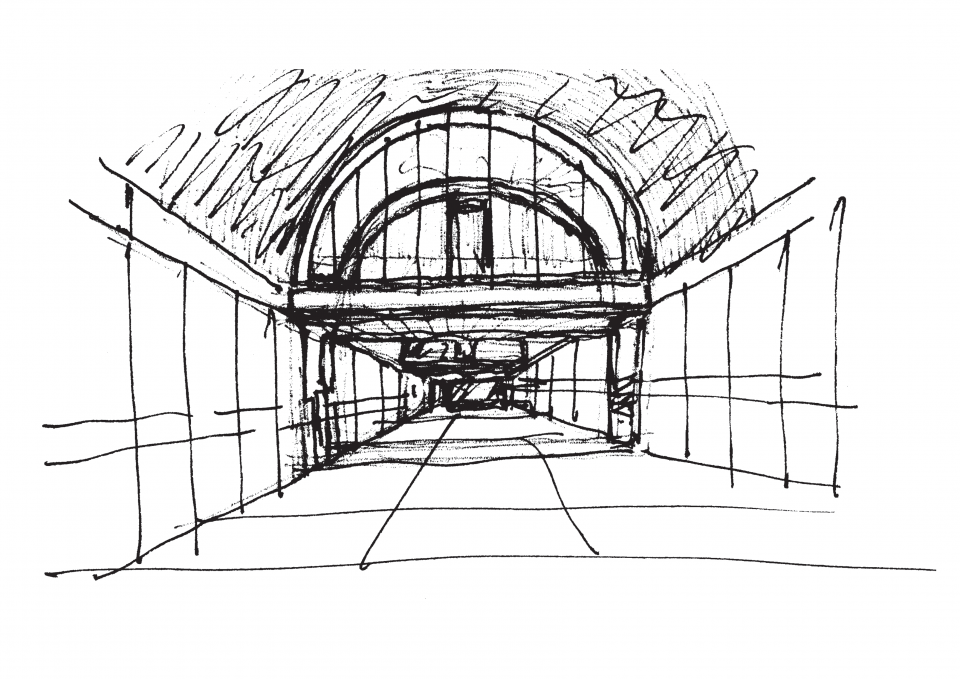

A longitudinal section hints at the way that single, double and even triple-height spaces flow into each other. At Sangath, Doshi has drawn together a number of themes from his earlier work — vaults on walls, platforms and terraces, maze-like interiors, ambiguous edges, dynamic sequences of structure — to serve a rich blend of ideas.

(Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India; William J. R. Curtis)

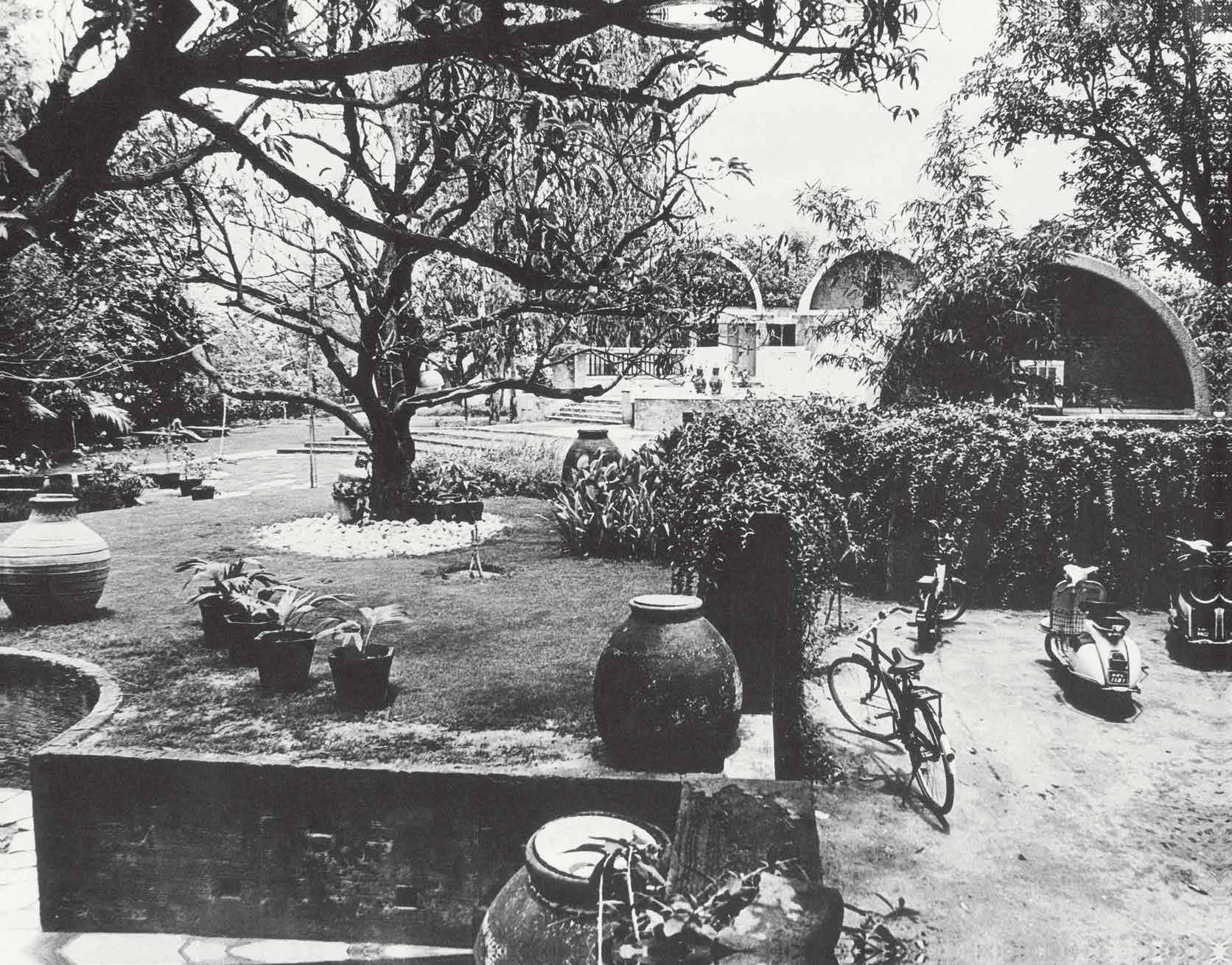

Before unravelling the intentions behind Sangath it is best to have an idea of how it feels to walk through the building. The first view is from the gate along a south-north line. A vault is seen head on, its curved silhouette hovering mysteriously at an uncertain distance behind and above a wall. A small rectangular opening in this wall gives a glimpse of the shaded interiors. The architect has spelt out the axis of the scheme but he then denies it, since one is forced to the left into a shallow valley which runs between a waist-high partition wall and some grassy mounds. Within moments it is possible to see the vaults on the diagonal, their low humps receding in perspective above a stratified foreground of steps, water channels and terraces. A niche cut into the garden wall echoes the curves of the vaults, as if one of them had been flipped into plan. Giant clay water jars squat in the long grass, their bulbous shapes, incised patterns and curled rims hinting at the source of the “peasant” forms behind them. Doshi has started the procession with a rustic address, and the theme is intensified by a sequence of stepping ponds reflecting the building in their still surface. Here the line of approach is clear: it is a diagonal axis leading up the shallow steps. Correspondingly the path turns, led around by the curved edge of the pool.

(Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India; William J. R. Curtis)

For its creator, the building is also soaked in Indian associations — not obvious quotations so much as hermetic allusions — and these add richness to the forms. Doshi has often referred to the way in which temples are organised with stages rising to a plinth, from which the superstructure continues in facetted forms. Among his doodles there are some comparing the curves of Sangath to stupa forms and even to head-dresses. The ambiguous relationship between figure and ground, built-form and external space embodies Doshi’s notion of transitional places for multiple use. The circuitous path and shifting axes fit the preoccupation with processions through traditional complexes, while the staccato rhythms on the interior follow on from the spatial conceptions of IIM Bangalore.

(Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India; William J. R. Curtis)

In fact there are two ways in, and the one most often used descends a few feet under the cover of a vault before encountering yet another choice: either a flight of steps which rise up through a triple-height volume or else yet another turn to the right, along a narrow passage. This passes Doshi’s own office and then continues into the main drafting room under the vaults. As one enters this long space there is a sense of release upwards. The undersides of the vaults are in textured grey concrete and this distributes a restful light broken in places by alternating bands of shadow. At the far end is the alluring rectangular window seen from the gate in the first view. If one turns 180° there is a similar window at the end of the passage, with a small clay statue framed in it. The main axis, for some time lost, is thus reaffirmed. To one side, steps lead down into a subterranean meeting room with a diagonal perimeter. It corresponds to the stepping amphitheatre above — also a communal place.

(Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India; William J. R. Curtis)

It comes as no great surprise to learn that in his own studio Doshi should have tried to evoke a small rural settlement. One of the earliest studies for Sangath was done soon after a visit to Egypt, where Doshi was impressed by domical forms in the village of Harania as well as by the vaults of the Crafts Centre by Wissa Wassef. In theme and form Sangath is a descendant of ATIRA houses, but now the communal space is more clearly articulated by means of the little theatre. The scale is very accommodating and the platforms encourage people to sit, to chat or just to contemplate a garden that is full of trees, flowers and birds. The turf mounds rhyme with landscape over the road, and this visual connection serves to underline the rusticity of Sangath still further.

(Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India; William J. R. Curtis)

The form and interior organisation of Sangath express the response to climate directly. The building dramatises the natural elements of land, sky, sun, rain. India possesses many subterranean or half-buried building types and in Gujarat there are varieties of stepped-well. At Sangath Doshi has invented his own procession into the earth. The interiors are further insulated by clay fuses within the vault structure. Western sun is absorbed by the grassy mounds; heat and glare are reflected off the white china surfaces. When the monsoons crash down they sluice easily over the shiny curved surfaces into gutters that gurgle into troughs. The sun makes deep-cut shadows under the white rims of the vaults and on the interiors light is baffled by slots and skylights to cast a restrained glow. At night the moon twinkles on the china mosaics and is reflected in the water — Sangath articulates Doshi’s private dream of harmony between individual, community and nature.

(Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India; William J. R. Curtis)

Other projects by Balkrishna Doshi