Cottrell & Vermauelen, Notre Dame School Extension, London

Fuente:Cottrell & Vermaulen, BD

Fotografía: Tom Cronin

The order of Notre Dame has occupied the school’s site in Southwark since the establishment of a convent there in 1855. St George’s Roman Catholic Cathedral stands 100m to the west and the nuns were initially tasked with establishing an associated school. It expanded rapidly, with its major buildings built in 1892 and 1937, and today functions as a voluntary-aided comprehensive school providing an education for 630 girls aged between 11 and 16.

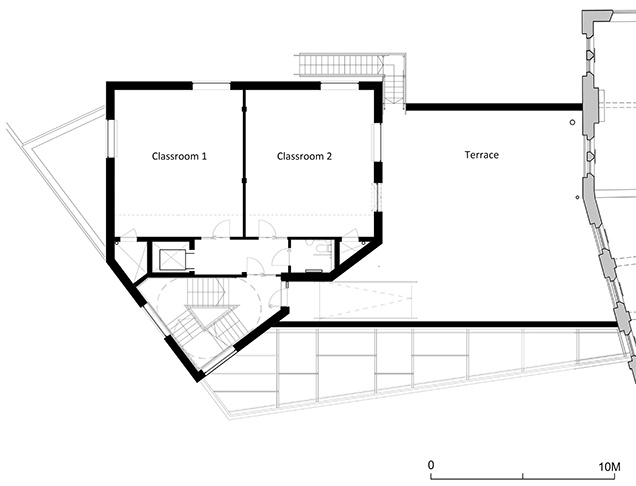

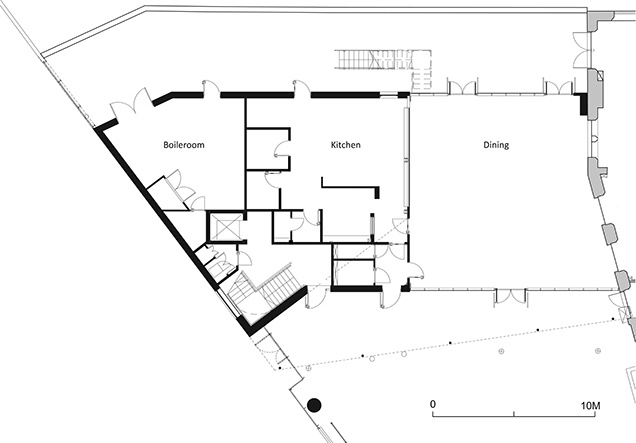

The latest building houses a dining room and café on its lowest level which is used by the whole school. Its upper floors, however, are the sole preserve of the 11-year-old Year 7 intake. As such, these floors function effectively as a school within the larger school — a base enabling the youngest students to make a gentler transition from their primary to secondary education than they might otherwise enjoy.

The school has access to playing fields in the park that lies on the opposite side of St George’s Road but its own site was already so fully occupied as to leave just one location available for expansion: a triangular forecourt that takes up a rather inexplicable change in geometry between the school’s five-storey primary elevation and the street.

In its former incarnation as a car park this was not a memorable space but as a building plot it presented an opportunity to create a structure of considerable urban drama.

Positioned adjacent to the school gate, the four-storey building has a lodge-like presence — a smaller but more ebullient offspring of the long slab of Victoriana that extends behind it. It provides the school with a more effective relationship to St George’s Road, functioning as a landmark visible down much of its length, but thanks to the presence of the park to the south and a railway cutting to the north the project also commands views over a much wider territory.

Two public institutions — the cathedral and the Imperial War Museum — lie at a distance but within direct view and modestly dimensioned as it may be, the new building strives with some success to draw them into a considered ensemble.

That ambition is reflected in a facade treatment of striking monumentality. Early iterations of the design toyed with the use of ornamental banding in the manner of Adolf Loos’s Josephine Baker House but the built scheme is altogether more chaste, relying for much of its effect on the relationship between just two materials: brick and glass.

The brick is the same Ibstock Heritage Red Blend that the architect employed to great effect in its expansion of Brentwood School in Essex and, as there, it is handled with the aim of emphasising the homogeneity of the wall surface. The mortar is flush finished and offers a close colour match to the brick, while the use of a running quarter-bond places further stress on the surface’s cohesion.

The effect is well judged in relation to the building’s boldly sculptural form. The upper levels describe an asymmetrical pentagon in plan with the effect that from key angles, the passerby is presented with three facades rather than the usual two.

Accommodating the non-orthogonal geometry required the on-site manufacture of cut-and-glued brick specials but the continuity of the wall planes is maintained very persuasively. The sense is as if the building has been carved — like a Jack-o’-lantern, perhaps — out of a single material.

This cohesiveness is further enforced by the treatment of the windows. They come in two sizes — a larger white-framed type that is fixed, and a smaller black-framed one that opens — but are united in their consistently square proportion and free distribution.

The handling of the street elevation does introduce a degree of hierarchy to this otherwise determinedly unemphatic composition but the distinction is a subtle one. This facade has been loaded with the principal staircase enabling the windows to be located with still greater freedom than elsewhere.

The architect has also taken the opportunity to cluster a number together to create one very large opening — a gesture that offers a mannerist subversion of the building’s hard-won sense of solidity at its point of greatest prominence while exposing to public view the drama of dozens of schoolgirls tearing down the staircase each break time.

The Year 7 students are in fact the only Notre Dame girls who have access to external space outside games time, on account of the decision — hotly contested by the Year 11 girls — to provide them with exclusive access to the roof terrace above the café and dining room.

And yet, despite its focus on the needs of the youngest girls, the scheme does offer significant dividends for the entire school. Where the kitchen and dining facilities were previously at basement level, they are now liberally day-lit and the chef even has access to his own herb garden. Takings in the café are up by 40%. In relocating these facilities it has also been possible to create a much improved suite of music and drama studios in their place — a facility that is particularly valuable given the school’s weekend role as one of the bases of the London-wide Centre for Young Musicians.

The project was delivered within Southwark’s BSF programme, a process that Sister Anne Marie maintains was “incredibly bureaucratic and frustrating because the rules kept changing” but which she acknowledges has enabled her to realise a building of considerable architectural and pedagogical particularity. Unsurprisingly, she is dismissive of calls for greater standardisation.

“We have built a bespoke product within the financial framework,” she says. “You can’t have a one-size-fits-all solution. Every school has different needs. The way we have done it might not have worked, for example, for a mixed school.”

The quality of the internal finishes is particularly striking and clearly a testament to Sister Anne Marie’s close involvement. Her research involved visiting an extensive list of precedents, including a number of non-academic environments such as the offices of Apple and PwC. She notes with pride that the chairs in the café are Fritz Hansen originals and describes taking students to design showrooms in Clerkenwell to find fabrics that will last.

Some of these features have required the school to find additional funds beyond the sum allocated by Southwark but much has been achieved by making savings elsewhere. Whether such strategic thinking has any place in Michael Gove’s brave new vision of school procurement sadly seems doubtful in the extreme. Perhaps our only hope is that the estimable Sister Anne Marie Niblock might be persuaded to give him a piece of her mind.

Architect:Cottrell & Vermeulen Architecture

Client: Southwark 4Futures,Balfour Beatty Construction Services

M&E contractor: Balfour Beatty Engineering Services

Structural engineer: Haskins Robinson Waters

Mechanical electrical & public health: Wallace Whittle

CDMC: Aversion

Building Control: HCD Building Control

Fire: Fusion Fire Engineering

Breeam: Ferguson Brown

Other projects by Cottrell & Vermauelen